CME & FanDuel: The Casino is Open

August 2025

Growing up, I always struggled to convince others that investing was not the same as gambling; my grandfather would often remark that the stock market was no different than the casino. I would just shake my head and think that he was naïve. Sure, there were still retail day traders, penny stock pump and dumps, and a general air of grift amongst retail gurus, but the world was relatively insulated from it all.

However, years later during pandemic lockdowns, things started to feel a little different. The casino was closed, but the market was open. I watched as friends—who had never shown any prior interest—became hooked on trading highly risky 0DTE options and memetic cryptocurrencies. It was a brave new world: Tesla calls paired with S&P 500 puts, Dogecoin, Discord chat room subscriptions, GameStop, AMC, Bored Ape NFTs—none of these words are in Security Analysis! However, as the era of free money began to wane and asset prices fell, this risk-seeking attitude also diminished.

Retail interest has ebbed and flowed over the last few years, but today it seems to be nearing its pinnacle yet again. Something in particular caught my attention this month: our own CME announced a partnership with FanDuel to introduce market-related event contracts on their gaming platform.1 While betting the over on Kentucky Football, you can now also lose money by betting on the daily closing price of the S&P 500 without ever leaving the FanDuel app. If this goes on for any longer, I will have to say that Grandpa was right.

Bucket Shops

So, how did we get to this point? Or, really, have we always been here? In the 1800s and early 1900s, the public wagered on the rise and fall of assets in establishments known as bucket shops. In 1906, the Supreme Court defined a “bucket shop” to be “an establishment, nominally for the transaction of a stock exchange business, or business of similar character, but really for the registration of bets, or wagers, usually for small amounts, on the rise or fall of the prices of stocks, grain, oil, etc., there being no transfer or delivery of the stock or commodities nominally dealt in”. Bucket shops were effectively casinos masquerading as legitimate brokerage firms, with no actual trading taking place. They usually offered excessive leverage, sometimes as high as 100:1, and customers often lost all of their initial capital. These operations were effectively banned after the Martin Act in 1921.2

Over one hundred years later, not much has changed. The public is still captivated by the excitement of financial markets. Event contracts are not quite the same as bucket shops—FanDuel is not claiming to be a traditional brokerage, nor is “The House” on the other side of the event contract—however, the essence of the activity is all the same. Today, retail traders are increasingly attracted to products that increase their potential returns, but at the same time increase their risk of ruin. Event contracts typically have all-or-nothing payouts with a defined expiration date. Stock options, which continue to become more popular as a trading vehicle, are similar in that they also have a high chance of expiring worthless and are attractive to many due to the leverage they provide. Even more, leveraged single-stock ETFs, a relatively new product, continue to increase in popularity among primarily retail traders who want more exposure to already volatile stocks. The vehicles are changing, but the general attitude is not: “Get me as much leverage as you can”.

Psychology

As it turns out, despite the various warnings from the past, human nature has proven to be immutable. We are psychologically predisposed to react strongly to our anticipation, rather than the actual outcomes. Jason Zweig details the experience of having his brain activity scanned while playing an investing game in his book Your Money & Your Brain:

“Learning the outcome of my actions, by contrast, was no big deal. Whenever it turned out that I had clicked at the right moment and captured the reward, I felt only a lukewarm wash of satisfaction that was much milder than the hot rush of anticipation I’d felt before I knew the outcome. In fact, Knutson’s scanner found, the neurons in my nucleus accumbens fired much less intensely when I received a reward than they did when I was hoping to get it.”3

It’s no wonder that the excitement of high volatility and leverage continues to draw interest from casual observers. Particularly in the age of social media, where large gains are posted online for everyone to see, how could inexperienced investors not anticipate anything other than similar gains? Worse yet is the confidence bestowed upon novice investors in a bull market. When risk taking is rewarded with positive outcomes, an investor’s appetite for risk grows. Behavioral economists Richard Thaler and Eric Johnson studied this in their 1990 paper “Gambling with the House Money and Trying to Break Even: The Effects of Prior Outcomes on Risky Choice”.4 What they found in their various experiments was that risk-seeking behavior increases after an individual experiences a win under similar circumstances. Their findings suggest that individuals are much more willing to gamble what they view as “house money” as opposed to their initial capital. Unlike casino games, however, all else equal, temporaneous gains in an asset inherently reduce the expected return going forward, making this effect all the more irrational in financial markets.

Other Signposts: Quality vs High-Beta

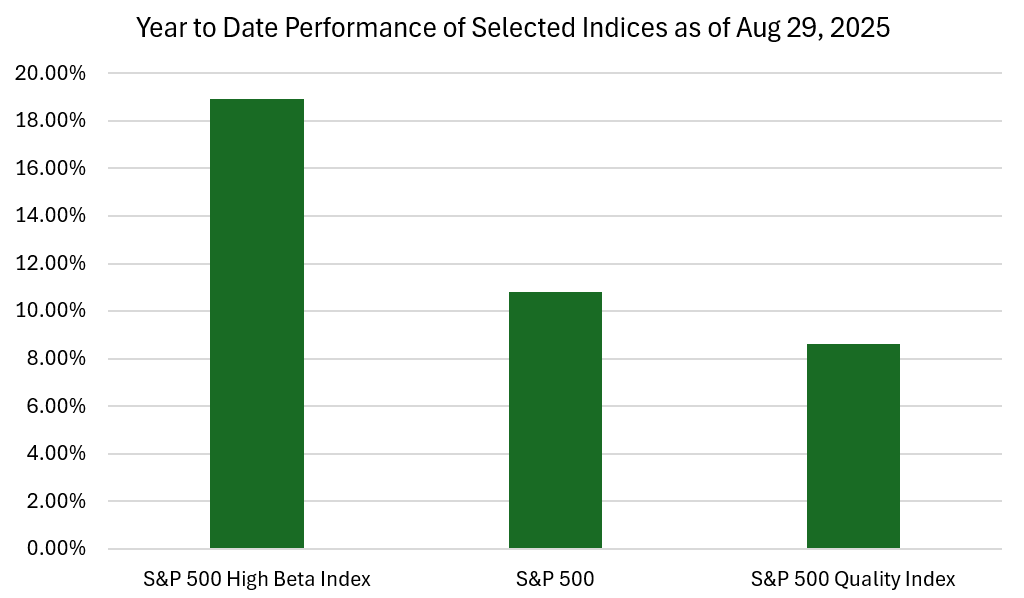

Currently, there is ample “house money” floating around, and it has not only been restricted to the retail derivatives market. Equity investors have been in a frenzy after coming off strong returns in 2023 and 2024. As I mentioned last month, crowding into high-beta stocks is at historic highs, suggesting a strong preference for risky investments. Year to date, the S&P 500 High Beta index has increased by nearly 19%. This compares very favorably against the S&P 500’s return of ~11%, and even more favorably against the ~9% return generated by the S&P 500 Quality Index, which tracks the performance of highly rated companies based on profitability, balance sheet quality, and earnings quality.5 Conversely, stocks with higher betas tend to be riskier and are often favored during risk-on environments.

Not only are there signs in the equity markets, but credit spreads also paint a similar picture. Shown below is the ICE BofA US High Yield Index Option-Adjusted Spread, or more simply, the additional rate of return investors are demanding for lending to financially risky companies:

As seen above, investors are accepting historically low yields for risky credit. Are investors at large seeking to take on more risk? It certainly seems that way to me.

However, just because the gyrations of the market feel more and more like the rollercoaster of the casino, it does not mean that investors must behave as if they are at the roulette table. Now, more than ever, it seems appropriate to heed the advice that the market exists to serve intelligent investors, but not necessarily to guide them. Understanding why these moments of euphoria happen also helps us, as investors, have patience when the rest of the market is telling us to throw caution to the wind. The temptations are normal. Not giving into them is what is abnormal. We are sticking to our long-term perspective and maintaining patience in the current environment.

Endnotes:

- https://www.cmegroup.com/media-room/press-releases/2025/8/20/cme_group_and_fanduelpartnertodevelopinnovativeeventcontractspla.html ↩︎

- https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/bucket_shop ↩︎

- Zweig, J. (2007). Your money and your brain: How the new science of neuroeconomics can help make you rich. Simon & Schuster. ↩︎

- Thaler, R. H., & Johnson, E. J. (1990). Gambling with the house money and trying to break even: The effects of prior outcomes on risky choice. Management Science, 36(6), 643–660. ↩︎

- Not an investment recommendation. References to indices are for illustrative purposes only. Please see https://www.spglobal.com for more information regarding index methodology and construction. ↩︎

Important Disclosures

This page is provided for informational purposes only. The information contained in this page is not, and should not be construed as, legal, accounting, investment, or tax advice. References to stocks, securities, or investments in this page should not be considered investment recommendations or financial advice of any sort. Appalaches Capital, LLC (the “Firm”) is a Registered Investment Adviser; however, this does not imply any level of skill or training and no inference of such should be made. All investments are subject to risk, including the risk of permanent loss. The strategies offered by Appalaches Capital, LLC are not intended to be a complete investment program and are not intended for short-term investment. Any opinions of the author expressed are as of the date provided and are additionally subject to change without notice.